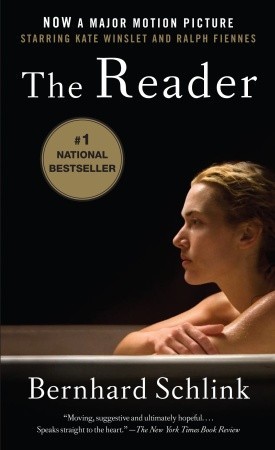

The Reader

The ReaderBernhard Schlink

Translated by Carol Brown Janeway (from German)

Originally 1995, I read 2008 Vintage Movie Tie-in

218 pages, historical fiction, romance, moral conundrum

When Michael Berg is 15 years old, he falls in love with a mysterious woman in her mid-30s named Hanna. While they become lovers and she finds out about his life and school, she is hesitant to say anything about herself or her background. Besides sex, what brings them together is her desire to listen as he reads books to her.

She disappears without warning, leaving him bereft and lonely. The next time he sees her is a shock: she is on trial for war crimes committed while she was an SS officer at Auschwitz. He follows the trial closely, but he cannot reconcile his memories of her with the evidence presented. Is she hiding an even bigger secret than those she is accused of? And what does it mean that he had loved someone who could do such terrible things?

Read on Kindle or buy from Amazon:

Guilt, national and individual

When I began this book, I thought it was a novel about a teenager's romance with an older woman and the fallout that it has in his life. So you can imagine my surprise when I suddenly discovered that it was a meditation on the guilt that Germans, as a country, (should?) feel about the Holocaust, as well as a love story.

Is it a love story? Or is it a guilt story? Although Michael doesn't say that he feels guilty about his romance with Hanna, it has a serious impact on his life. All of his later relationships are shaped by his experiences with her, and he is never satisfied with another woman because they aren't her. And then when he discovers who she was and what she did during the war, he questions who he is that he could love a person like that.

Schlink beautifully parallels this personal exploration with the communal angst of the German people, especially those who were born after the war. What were they to think of the fact that their parents and other family members committed these atrocities, or, if they did not actively participate, turned a blind eye to the genocide that occured nearby? What could make someone do that to another person? And could it happen again? Were they capable of it as well?

Methods to escape from guilt

How does one escape from such an all-consuming guilt? The narrator searches for an answer, but falls further into depression and detachment. He becomes numb, numb like the officers that worked in the concentration camps: unable to feel anything.

Hanna finds her own way to deal with the guilt: in the trial, she admits to what she did without any attempt to conceal the truth. Later, in prison, she occupies herself with the tasks she is given and keeps her mind busy. And finally, toward the end of the book, she tries to learn as much as she can about what happened during the Holocaust, about the people that died and the people who worked in the camps. Although the author does not mention the reason for this, Hanna was probably trying to understand how everything happened and how she became involved in it.

Both of the parallel stories leave us in a limbo. We must move on and deal with the guilt, understand and condemn at the same time. But how?

No comments:

Post a Comment